Stroke can cause unique speech problems; two common ones include Broca’s aphasia and Wernike’s aphasia. This post explores those two and how stroke creates them.

Let us begin with Broca’s aphasia.

Broca’s aphasia

This type of speech problem occurs due to a stroke attack in Broca’s area.

Where is it located?

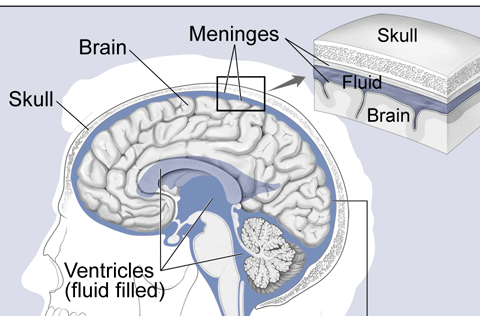

Broca’s area (Figure 1)

The Broca’s area rests on the lower part of the left Frontal lobe. I invite you to re-visit the Journeys to the brain: 2 – A walk over the brain surface which introduces different brain lobes. For easy reference, I have included a graphic that appeared in my earlier journey to the brain.

Figure 1: Broca’s area

Source: Polygon data were generated by the Database Center for Life Science(DBCLS)[2] under the license of CC BY-SA 2.1JP through Wikimedia Commons

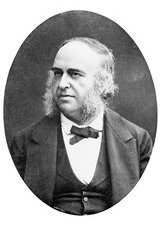

Paul Broca

Before 1861, scientists debated whether the whole brain acted as a single entity or contained specific regions. Pierre Paul Broca ended this debate in 1861 (Figure 2)

Source: Wellcome Collection under the license of CC BY 4.0

“Monsieur Tan”

Before 1861, Pierre Paul Broca examined an adult male – Leborgne – who came with right-sided paralysis.

Pierre Paul Broca was a surgeon with a special interest in physical anthropology. He had been studying the association between skull shapes and sizes with evolution.

In addition to Leborgne’s – Broca’s patient – right-sided paralysis, he was suffering from another problem. He produced only one sound with one syllable – “tan” twice in-succession. He was ok with understanding. Since then, the hospital staff identified him as “Monsieur Tan”. Paul suspected Leborgne’s problem was due to some damage to the brain’s left side/ After his death, Paul dissected his brain and discovered a damaged region in Leborgne’s brain’s lower part of the left Frontal lobe. You can read more about this in Broca’s region article.

In 1861, Paul Broca presented his findings – “our brain owns a specific area in charge of speech production” – to the world.

Three years later, Broca described 25 similar cases. All but one had a damaged area at the same place in the brain: the lower part of the left Frontal lobe – just above the left eye’s orbit.

With that, he ended the great debate at that time: “The brain owns specialized areas for specific functions”.

However, now, we know that this is not 100% accurate.

Since then, the medical community has continued to name this area in the left hemisphere as “Broca’s area” to recognize his exemplary work. And, the inability to produce speech as a result of damage to this area is named “Broca’s Aphasia”.

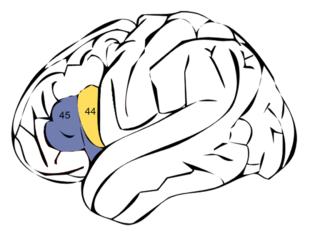

Brodmann 44 and 45

Much later in 1909, another expert – Brodmann – identified two parts of Broca’s area. These parts were named Brodmann 44 and 45 which are depicted in the following sketch (Figure 3).

However, most recently, researchers, using sophisticated MRI technology, showed that Leborgne’s brain damage had gone beyond what we now have typically known as Broca’s area. This fact raised doubt about the exact role of Broca’s area in speech production.

Using the latest technological advancement, researchers have shown that Broca’s area mediates the interaction between the Temporal lobe which helps us to process listening, and the motor area of the Frontal lobe, the area that sends signals to speak.

How a stroke causes Broca aphasia

A full-blown stroke blocks the brain’s blood supply. When it happens inside the anterior branch of the middle cerebral artery, the brain cells in the Broca area are deprived of oxygen and nutrients. As a result, they begin to die each passing second at a rate of about 32,000 neurons per second! The final result is this particular speech problem.

What happens here?

Do you remember Paul Broca’s first patient? – Mr Leborgne who was named “Monsieur tan”? He managed to talk only one word – “tan”. However, as in the case of “monsieur tan”, those with Broca aphasia do not lose speech completely; they can speak a few meaningful words at a time. And, they can read and understand too. This is completely different from Wernicke’s aphasia.

Let us find out what those living with Broca aphasia can and cannot – or have difficulty with – do. These problems become more pronounced when the block happens on the

What those living with Broca aphasia can do

- They can hear.

- They can read.

- They can understand simple – not complex – instructions.

What they cannot (or are difficult) to do

- Talk only less than 4 – 5 words at a time

- They can talk by simulating telegraphic speech.

- The sentences lack grammatical sense – both in talking and writing.

- Use nouns without verbs.

- Have difficulty in repeating.

- Can’t respond to complex instructions: for example, touch nose after touching toes.

Do you want to know what Broca’s aphasia looks like? Watch this YouTube video.

What is the usefulness of knowing these things?

- Knowing different types of stroke aphasia helps stroke carers create communication methods with their loved ones.

- What they can or cannot do within a few days after the stroke helps predict the area/s of the brain affected, where neurons are dying as highlighted in the paper by Elisa Oschfeld et al.

- The brains of many with Broca’s aphasia do not allow them to live with those problems long; recovery can be immediate due to the restoration of blood flow as shown by Cameron Davis and their research team.

- Or else, it may happen later possibly due to the execution of the brain’s plan B – reorganizing adjacent neurons to take over the dead neurons’ job as speculated in the paper by Elisa Oschfeld et al..

Wernicke’s aphasia; “Fluent aphasia”.

This journey travels through this speech problem that stroke can cause: Wernicke aphasia. It is also called “fluent aphasia”.

In 1874 – after Paul Broca discovered the Broca area and Broca aphasia – Carl Wernicke described a different type of aphasia. This type allows the affected to talk at their usual speed, but words and sentences do not convey meaning. Anyone can notice the problem. And, they repeat the same over and over again.

According to Argyle E. Hillis, they seem unaware of their errors. The listener might think that the affected are talking in another language that the listener cannot understand. Not only talking but writing and reading follow a similar pattern. Hence, this type of aphasia is called fluent aphasia (Broca aphasia is called non-fluent aphasia). Since Carl Wernicke described this, it is also called Wernicke aphasia.

You can find out how an individual with Wernicke aphasia converses with others by watching this video clip.

The Wernicke aphasia occurs as a result of damage to the Wernicke area. Where is it in the brain?

Wernicke’s area

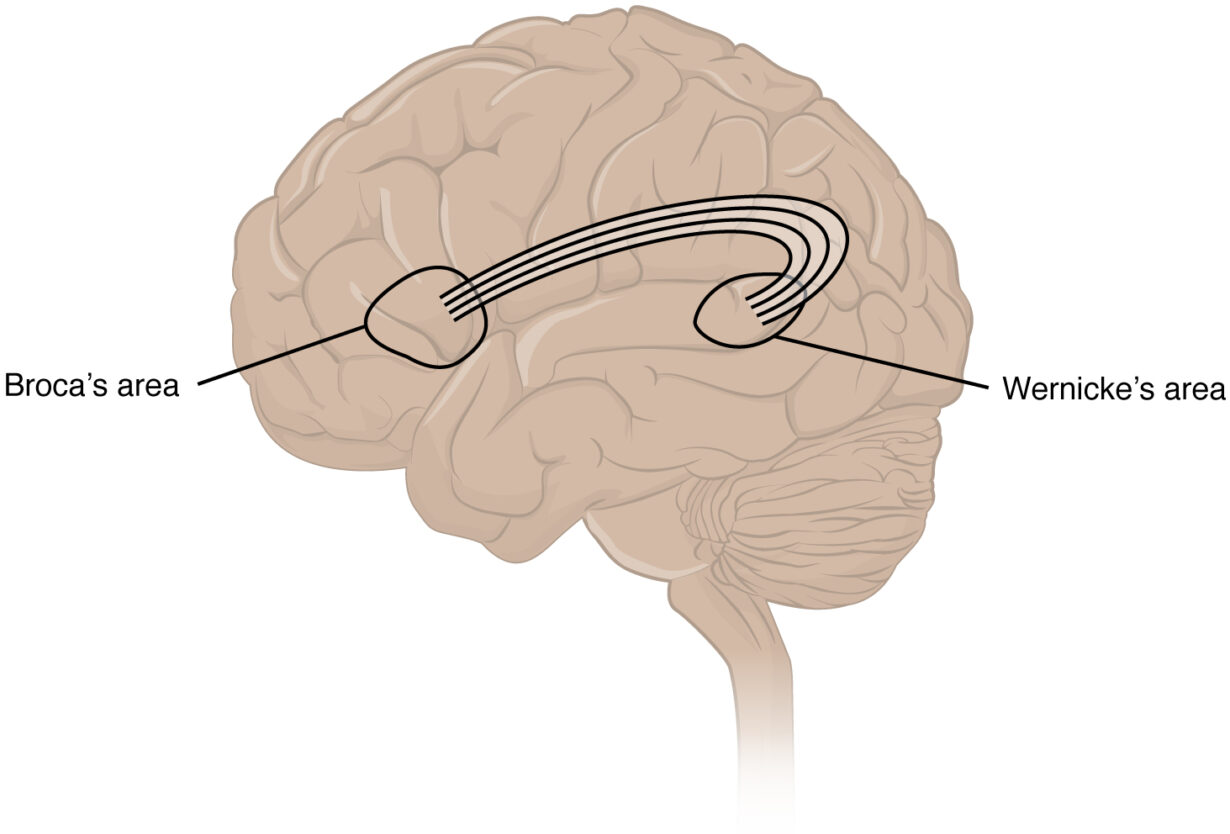

The Wernicke area lies in the temporal lobe. You can find the temporal lobe in this walk over the brain surface in the journeys to the brain – 2. The Wernicke area lies close to the area (auditory) that contains cells specialized in processing hearing information (Figure 1). Whenever we hear something, the hearing area receives information from the ear and then sends it to the Wernicke area. Similarly whenever we see or read something, the visual area sends that information to the Wernicke area. Neurons in this area retrieve suitable nouns appropriate to the context from the storeroom, set the language structure, and shoot that to Broca’s area. Broca’s area processes it to produce speech.

How do Wernicke’s neurons connect with Broca’s neurons?

As shown in Figure 4, Wernicke neurons connect with Broca’s neurons through a super-highway, called “arcuate Fasciculus”. This bundle of neurons transmit messages between the two speech-processing areas.

Figure 4: Wernicke’s area

Source: Polygon data were generated by the Database Center for Life Science(DBCLS)[2] under the license of CC BY-SA 2.1JP through Wikimedia Commons

How do Wernicke’s neurons die?

Wernicke’s neurons die due to disrupting the blood supply to the temporal lobe where the Wernicke area resides. Most commonly, a blood clot that blocks a branch (the inferior branch) of the left middle cerebral artery is the culprit.